Introduction

The 1920s inspired those with courage or hard cash (or connections to it) to forge a world that only superlatives could describe. The “War to end all wars” was won, and the powers of politics, science and industry to erase man-kind’s other ills were in evidence:

- Women had the vote

- devil rum” was shackled

- Two army pilots flew across America non-stop in less than 27 hours

- Now, more Americans lived in cities than on farms (after all, they had seen Paree’)

- Jack Benny and Eddie Cantor commanded vaudeville, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, Eugene O’Neill, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot and Sinclair Lewis reshaped our literature

- Knute Rockne’s “Four Horsemen” dominated college gridirons, and the National Football League was formed.

- The world’s first commercial radio station, Detroit’s 8MK (now WWJ), went on the air, and a patent was sought for an electronic television transmitter.

A gay, glorious era for flappers, marathon dances and singing, “Yes, We Have No Bananas”. The Teapot Dome oil scandal and the re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan were forced to compete with the popularity of Babe Ruth and Winnie-the-Pooh. A clumsy attempt to overthrow the German government, the Beer Hall Putsch, was dismissed as the political escapade of an eccentric malcontent, Adolph Hitler.

This was also a time for building. Detroit’s Penobscot Building, the General Motors Building, the Fisher Building, the Detroit Public Library, the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, Masonic Auditorium, the Buhl Building and Police Headquarters on Beaubien were only part of the construction that was reshaping Detroit’s skyline.

In this climate, John W. Austin approached financier Joseph A. Bower, a Detroiter, in Bower’s offices at the Liberty National Bank in New York City. Austin was an officer of the Detroit Graphite Company, and his aim was to secure a contract to paint such a bridge as might, inevitably, span the Detroit River. Their meeting spawned a remarkable accomplishment – a $23.5 million, privately financed link between the United States and Canada. As the two men met above the din of Manhattan’s streetcars and crowds, they talked of heavy construction and high finance. They could not have foreseen their role in a most curious event in Detroit’s history.

Efforts in vain

The development of Great Lakes shipping, inaugurated by French trappers three centuries before, intensified in the industrial age with the demand for iron ore and other resources of the region. In 1872, the Great Western Railway sent a survey team to Detroit to test the feasibility of a drawbridge, but well-established shipping interests and the ferry boatmen thwarted the plan.

Every conceivable site after that triggered a proposition for a bridge: across Belle Isle, a span from Woodward Avenue to Windsor. The Detroit Board of Commerce formed an International Bridge Committee in 1903. Canada’s Border Cities were also anxious to derive the benefits of a link with Detroit.

Fowler’s Fiasco

Shortly after World War I, a prominent New York civil engineer, Charles Evan Fowler, came forward with a proposal to build a bridge that would accommodate cars, trains, street cars and pedestrians. He organized two companies in the early 1920s – the Canadian Transit Company and the American Transit Company – and had gained the support of both Parliament and Congress for his franchise. His plans, though, were too ambitious. The rail approaches for the $28 million structure would begin a mile inland. Public guarantees for the financing would be needed. Its 110-foot center height would give only marginal clearance for shipping. But still, Detroit must have its bridge. At this point, Russell T. Scott organized an investment scheme for Fowler’s project that not only failed to get the bridge financed, but devoured $2 million of Scott’s own money. Among Fowler’s most-ardent supporters was John W. Austin. Determined that the river would be spanned, he approached C. J. Marshall, a principal of the McClintic – Marshall Company, a noted Pittsburgh engineering firm, to adopt the project. It was Marshall who arranged Austin’s introduction to Joseph A. Bower, the banker with a record for snatching success from the jaws of defeat.

Bower vs. Smith – The First Encounter

After studying the finances and construction of bridge projects in this country and in Europe, Bower took up the project late in 1924, purchasing options of the stock of the Canadian and American Transit companies (primarily because of the government authorizations). He appointed John Austin treasurer, retained McClintic-Marshall to engineer and build the bridge, and began securing the necessary endorsements from approving agencies and public bodies.

Negotiating any bureaucracy can be intimidating. Joseph Bower was merely proposing to build the longest suspension bridge in the world. It is a measure of the man that his proposal was accepted by the: President of the United States, Governor -General of Canada, U.S. War Department, Canadian Minister of Railways, State of Michigan, Province of Ontario, Lake Carriers Association, Dominion Marine Association, Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Waterways Commission and the Great Lakes Harbor Commission, in addition to the already-held approvals from the U.S. Congress and the Canadian Parliament. And on top of this, Bower arranged the financing. After gaining these approvals, Bower applied to local authorities for their consent. The town of Sandwich, Ontario, quickly concurred. Essex County, Ontario, held a spirited referendum in which the bridge project was approved by the voters.

In Detroit, an objection that the proposed bridge’s 135-foot clearance would limit future navigation was overcome after some protracted discussion. Bower would build his bridge 152 feet above the Detroit River. Thereupon, the Detroit Common Council unanimously approved the bridge’s construction.

But Detroit Mayor John W. (Johnny) Smith had yet to assert his authority. He cast his veto. The Council overrode it, and he countered in Wayne County Circuit Court with a petition for a restraining order, blocking progress on the bridge until a popular referendum could be held. Presumably, Joseph Bower and John Austin conferred again. Perhaps they recalled their first meeting several years before. They had come so far. The financing was in hand. The plans were drawn. The authorities had been satisfied.

Battle Lines

Mayor Smith’s opposition to the bridge was not totally capricious. He argued that, ultimately, the bridge’s users would pay for its cost and debt service, and would pay a perpetual profit to its owners.

BUILD THE BRIDGE

Smith faced re-election, and at the time needed to assert his position as a champion of the electorate. His ally, powerful Robert (Wildflower) Oakman, did not welcome competition for his real estate activities in northwest Detroit from the direction of southwest Ontario. But the pair might have gauged their opponent more warily. Joseph Bower knew that his support among the citizenry was as solid as the planned bedrock foundation of his bridge. Detroit’s political and business leadership was committed to the project. With customary thoroughness, every objection had been refuted or resolved. Bower declined to fight Smith in court. With bravado, he personally assumed the estimated $50,000 cost of the referendum.

The issue became a publisher’s bonanza. Full-page advertisements darkened newsprint in Detroit with charges and counterclaims. Smith and Oakman warned of the greed of the “Barons of Wall Street”; the signatures of Detroit’s first citizens were affixed in public support of the proposition; even merchants closed their ads with the motto: “Build the Bridge”. Public meeting fueled private debates. John Lodge, then a member of the Common Council, became a leading supporter of the bridge, and saw his mayoral candidacy enhanced.

The Essesltyn Affair

Finally, the eve of the election, Mayor Smith took to the airwaves for a final condemnation of the proposal. It proved his undoing.

As Smith was leaving the studio, he encountered H. H. Esselstyn, a highly respected engineer on the Belle Isle Bridge works, and, at the time, Commissioner of Street Railways. Esselstyn was about to broadcast a statement favorable to the bridge interests. Smith fired him on the spot. The professional was stunned by the politician’s vengeance. Nonetheless, he spoke into the microphone with a calm suited to his considered technical opinions, as he had prepared to do. Then, a pause, and this final sentence: “I want all Detroiters to know that because I have made this short speech, I have been discharged as Commissioner of Street Railways.”

Victory

The following day, June 28, 1927, 74,558 votes were cast, an extremely high turnout for such a special election. The bridge carried by an 8 to I margin. In October of that year, John C. Lodge defeated Smith in the mayoral primary election.

Construction

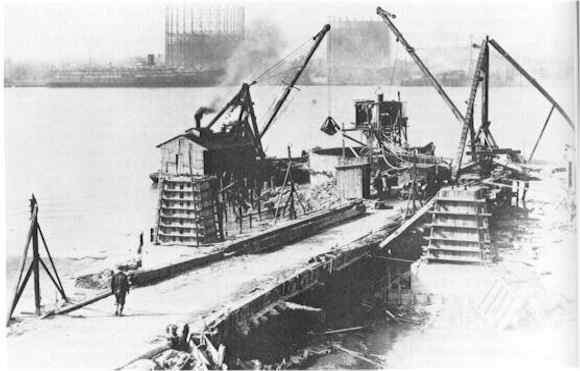

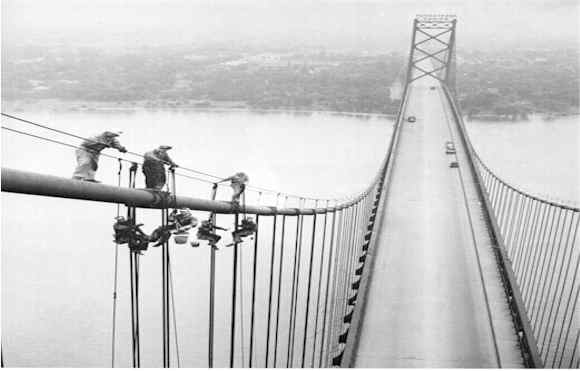

Construction had actually begun a month and a half before the referendum. Congress had ruled that construction would have to begin by May 12, 1927, or the bridge franchise would expire. Hoping that Congress would regard boring operations as a meaningful start of construction, Bower staged ceremonies May 7 with Austin’s 16-year-old daughter Helen driving the first boring stake into the ground to determine the depth of the bedrock.

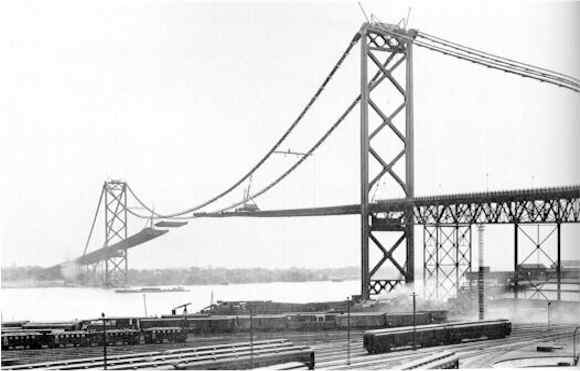

The general contract for construction was signed July 20, 1927, and made operative August 16. McClintic-Marshal was allowed until August 16, 1930, to complete the job. If it was not done by that date, the engineering firm would be liable for interest on the securities until the bridge began producing income. If McClintic-Marshall finished the job in advance of the deadline, they would be entitled to half the revenues between the date the bridge opened and April 16, 1930. Just over two years later – on November 11, 1929 – the Ambassador Bridge was ready for operation. McClintic-Marshall had brought the job in one percent.

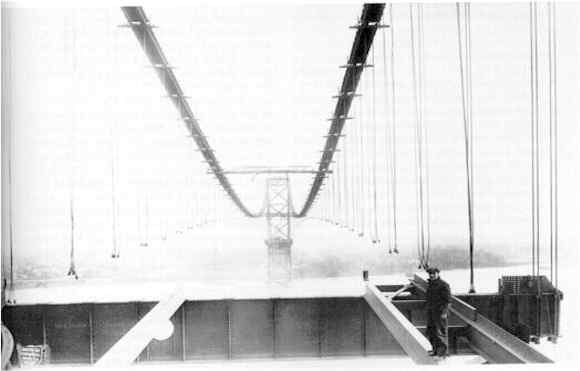

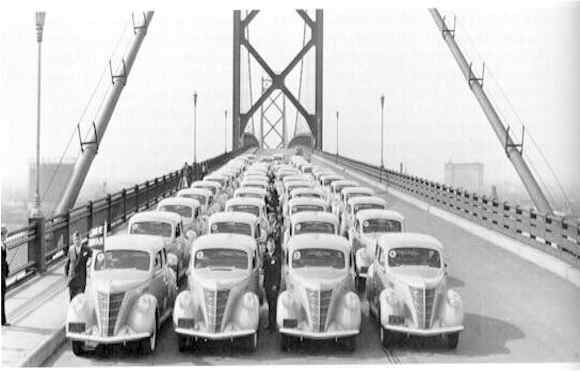

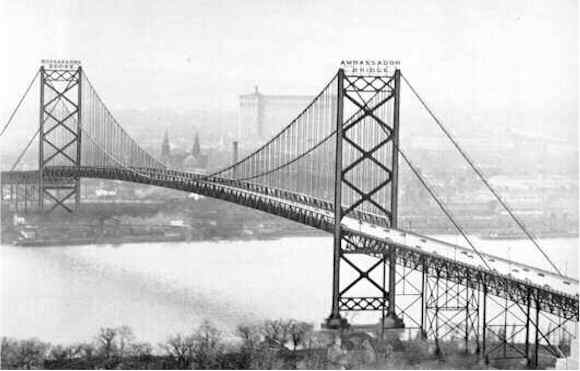

When the Ambassador Bridge opened for traffic four days later, its almost 21,000 tons of steel rose at never more than a five percent grade to an apex of 152 feet above the swift current of the Detroit River. Its 1,850-foot center span made it the longest suspension bridge in the world. Its total length was 7,490 feet, with the U.S. and Canadian terminals 1 3/4 miles apart. The roadway was 47 feet wide with an eight-foot-wide sidewalk on the west side. The twin silicon steel towers that rose majestically 386 feet above the ground were built on concrete piers resting on bedrock 115 feet below the surface. Close to two miles of cable within cable within cable – 37 strands, each as big around as a strong man’s biceps, each composed of 218 individual sinews of cold drawn, galvanized steel – had been erected. The main cables suspended between its two towers were fastened to massive concrete anchorages 22 1/2 feet wide and 100 feet long, sunk into bedrock 105 feet down. The cables – but not these cables – were also the most dramatic story of the construction.

The Changing of the Cables

The hissing of acetylene torches, the rasp of steel and the clatter of long lengths of cable being cut from the Ambassador Bridge to make room for stronger strands filled the air around the Bridge in the spring and early summer of 1929, just months before the Bridge would open. McClintic-Marshall had specified that the then-new heat-treated wire cables be used instead of the universally used cold drawn steel wire. The new heat-treated wire cables had been tested and found to have much higher tensile strength than the cold drawn steel wire used on the Brooklyn Bridge, for example, for 50 years.

These heat-treated wires had been woven strand by strand into the 37 component cables of each of the two massive main cables that would support the world’s longest suspension bridge, and by mid-February of 1929, the suspenders, like steel harp strings, had been hung from the cables and work had begun to fasten the steel framework of the roadway to the weighted ends of these suspenders. Progress on the Detroit River span was a whole year ahead of schedule.

But the up mood on the Ambassador Bridge turned sharply downward when word reached Detroit on February 22 that a number of broken wires had been found in the cables of the even more nearly completed Mount Hope Bridge in Rhode Island. This bridge shared with the Ambassador Bridge the distinction of being the first to use heat-treated wire instead of cold drawn steel. It came to light that three broken strands had been found near the Bristol, Rhode Island anchorage of the Mount Hope Bridge as early as January of 1929. Subsequent inspection on the Detroit River project revealed a few under any other circumstances, not an alarming number of broken wires in the Ambassador Bridge’s cables.

McClintic-Marshall, the same engineering firm that was building the Mount Hope Bridge, halted work on the Ambassador Bridge on March I and summoned a team of consultants from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to examine the situation and report. Based on that report, McClintic-Marshall – with full concurrence of Joseph Bower decided to absorb the half-million-dollar expense of removing the cables over the Detroit River and replacing them with time-tested cold-drawn steel wire. When the torches began hissing and the cutters began lopping the enormous cables into manageable lengths and lowering them to the ground, it was thought the entire year that work crews had gained on their three-year contract was hopelessly wiped out. But the old cables were replaced with new in time to hang the roadway and open the bridge on November 11 – nine months ahead of schedule.

A Hard First Decade

In the next few years, the Ambassador Bridge would be the site for a number of stunts: planes would fly under it, a man would parachute off it, a man would cross it walking backwards, another would push a friend across it in a wheelbarrow, a girl would toe-dance her way across it and couples would marry at its international boundary line. But the 1930s were the antithesis of the rotating ’20s.

The opening of the world’s longest suspension bridge had been preceded, just 21 days before, by the beginning of the crash of the New York Stock Exchange and the onslaught of the Great Depression. While almost 200,000 vehicles crossed the Ambassador Bridge during the remaining month and a half of 1929, and just over 1.6 million vehicles traveled it the next year, the left jab of the Depression was followed by a quick right cross with the opening of the Detroit & Canada Tunnel, linking downtown Detroit and Windsor under the Detroit River, just a year following the Bridge’s opening.

Financial Problems

Detroit International Bridge Company chairman and President Joseph A. Bower and his general manager, R. Bryce McDougald, former Windsor Collector of Customs, were faced with a competition for traffic that had not been projected or anticipated when the financial structure for the Bridge was originally planned. Compounding the problem were toll rates at the Tunnel much lower than what the Bridge could afford to offer. The competition from the Tunnel and Bridge also forced the ferries traversing the Detroit River to slash their rates 52 percent in an unsuccessful attempt to stay afloat.

Default

With traffic over the Ambassador Bridge dipping a half million in 1931, the bottom fell from the economic structure of the Bridge Company. It went into default on the interest on its debentures and the first mortgage bonds that year, just two years after it opened. The Tunnel also went into default, and its economic underpinnings sank.

As Bridge traffic slipped another quarter million in 1932, committees were established to represent the bondholders. Heavy taxes further crippled the Bridge Company’s ability to right itself financially. In 1932, taxes represented 80 percent of revenue, and continued in the mid – 70 percent range for the next three years. And traffic continued to fall through the Depression years. It increased somewhat from 1935 through 1937, aided by an increase in truck traffic encouraged by the completion in December 1937 of a new 20-door Canada Customs warehouse. But the increases in truck traffic were not enough to halt the mounting financial problems of the Bridge Company. By 1936, the accrued interest on the interest debt stood at $8,199,872 and climbing, in addition to unpaid taxes.

Reorganization

The savior of faltering businesses and bad debts, Joseph A. Bower, was now faced with the toughest challenge of his career: saving his own company. Through the final two years of the decade, he orchestrated a successful reorganization of the Bridge Company. The reorganization went into effect July 1, 1939, with the bonds and debentures exchanged for $133,089 in common stock by the end of the year, out of a total of 217,175 shares of stock issued at a dollar a share. And with the assets of the Bridge reduced to $2,600,000, a property reassessment also reduced Detroit and Wayne County taxes.

War Restrictions

But just as the Bridge was getting back its organizational and financial footing, another crisis hit: World War II. Travel was severely restricted during the War years, but truck traffic over the Ambassador Bridge continued to increase. Security measures established on the Bridge to deter anticipated sabotage included floodlighting, motor patrols, additional fencing and cooperation between police on both sides of the Detroit River. Both governments also assigned armed guards to duty on the Bridge.

And with the beginning of the War years, Canada placed strict controls on the movement of any Canadian funds out of the country. Under the Foreign Exchange Control Board, Canadian toll funds were restricted for use in Canada, and stayed with the Canadian Transit Company, the wholly-owned Canadian subsidiary of the Detroit International Bridge Company.

In 1941, traffic had increased over that of 1940, despite travel restrictions. The tolls were also increased for the first time since the Bridge’s opening. Gas rationing by 1942 cut back on car traffic, but truck volume rose by 12 percent, stimulated this time by a $21,387 addition to the Canada Customs warehouse.

During that year, the bridge’s first general manager during its operation, R. Bryce McDougald, died, and was succeeded by C. Clinton Campbell, a native of New Jersey, who was named assistant to the president. Within a year, he was elected vice president and treasurer. In 1946, he was named president, with Bower continuing as chairman.

Back on Solid Ground

In 1943, revenue from car traffic dropped 24 percent, but truck traffic continued its rise because of the increase in Customs warehouse facilities. With gross revenues up 28 percent in 1944, the first dividend in the history of the Detroit International Bridge Company was paid to shareholders. The 75 cents a share, paid within just five years of reorganization, would also be the first of an unbroken stream of dividends paid every year from then on.

The next year, 1945, two dividend distributions were made, totaling $1.25 a share, when revenues increased by 72 percent and earnings by 140 percent, caused in large part by U.S. resident travel to Windsor to buy gasoline and food items, both of which were in short supply in the U.S. during this War year. And for the first time since 1931, more than one million vehicles had crossed over the Ambassador Bridge. The practice of collecting tolls on the U.S. side, which began during the early War years as an economy and supervisory measure, was made permanent in 1945, and would remain the practice until 1973.

Post-War Prosperity

A 15 percent increase in traffic and revenue in 1945 and an increased capitalization allowed a 100 percent stock dividend plus a $1.05 a share dividend. Canada also started releasing some of the funds held by the Canadian Transit Company to the Detroit International Bridge Company.

Traffic and revenue continued to increase through the Bridge’s 20th anniversary year in 1949. In the first 20 years, more than 50 million people had crossed the Bridge, providing employment for hundreds in the Customs and Immigration services. Canada Customs duties collected over the years had averaged more than $15 million a year, and the average yearly value of commodities imported to the U.S. over the Ambassador Bridge from Canada had been $30 million.

The 1950s were a decade of continued steady growth in revenue and traffic for the Bridge, aided by boosts to truck traffic spotted throughout the decade: U.S. trucks were allowed to travel to Buffalo through Ontario (1952); a new Customs truck dock on the U.S. side was opened and, on the Canadian side, the Customs truck compound was enlarged (1953); and in 1955, the Canada Customs warehouse was increased in size by 50 percent.

IMPROVING THE BRIDGE

The closing year of the ’50s witnessed the retirement of Bridge founder Joseph A. Bower as chairman, after 30 years at the helm of the Bridge he built. In handing over the chairmanship to son Robert, he remained a director and change continued.

The Ambassador Bridge witnessed a repainting of all the toll plaza structures from black to green and white. The glossy black Bridge would have to stay black, though. An experiment in the late 1950s, in which a portion of the span was painted aluminum, found that the heavy downriver pollution quickly covered the bright aluminum paint with a sooty black.

With cooperation of Detroit and Windsor transportation departments, uniform Ambassador Bridge trailblazer road signs were designed and erected in the two cities to direct motorists to the Bridge.

Throughout the decade, further physical developments took place: Ammex Duty Free store opened on the U.S. plaza (1963); the office buildings were renovated to provide more space for customs brokers (1964); the Canada Customs office was doubled in size (1966); negotiations that would drag on for a decade were begun with the U.S. Government to enlarge the U.S. plaza (1968); and a large-scale rehabilitation program was begun in 1969, the Ambassador Bridge’s 40th anniversary, part of which saw the complete rewiring of the Bridge and the installation of new mercury vapor lamps and new electrical transformers.

In 1970, $850,000 was spent over a period of eight months in repairing the Bridge’s roadway. The U.S. approach roadway deck was rehabilitated by replacing some base concrete and installing a complete asphalt overlay, the first such replacement in the Bridge’s 40 years.

The original granite blocks, which had been embedded in sand to provide traction on the U.S. side’s five percent grade, were replaced with the asphalt paving. The blocks were given to the Windsor Parks & Recreation Department, and now grace many of the pathways in Windsor parks.

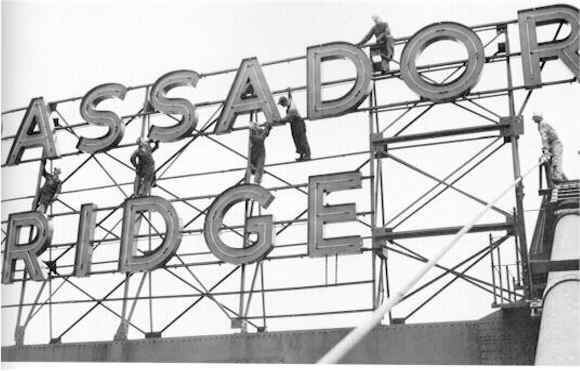

A rehabilitation of the Canadian roadway approach was completed in 1972, and new Canadian entrances and exits were completed to accommodate the new four-lane highway leading into the Bridge. A new U.S. toll plaza – with eight booths, islands and canopies and two 70 – foot, 150,000 – pound truck scales – was constructed in 1972, with comparable facilities also added on the Canadian side in 1973. 1973 also saw an extensive painting program, the paving of both terminals and construction of a new Ammex distribution and warehouse building on the U.S. terminal. The tower signs were also replaced that year at a cost of $33,000. Originally erected in about 1933, and replaced for the first time in 1952, each tower sign displays the words, “Ambassador Bridge”, in six-foot-high letters.

New secondary car inspection facilities were completed for Canada Customs on the Canadian terminal at a cost of $360,000 during 1975, and the primary inspection area was demolished and replaced with new, enlarged facilities at a cost of $325,000 the next year. Following an in-depth inspection of the Bridge structure, a special preventive maintenance program was inaugurated in 1976. The following year, the main cable band bolts were replaced for the first time as part of the program whose total cost approached $650,000. In 1974, a new retail sales store for Ammex was built on the U.S. terminal. In 1978, plans were made to install a $300,000 computerized toll system. But the president and general manager’s plans for expanding the Detroit plaza through adding a new terminal building for U.S. Customs truck clearance adjacent to the plaza were stalled through the entire decade by the lack of progress in negotiations with the U.S. Government’s General Services Administration.

The congestion on the U.S. plaza continued to mount as the decade progressed. By mid-decade, the Greater Detroit Chamber of Commerce and local municipal and county officials had entered into the negotiations to try to untangle the bureaucratic red tape impeding the expansion. In early 1977, the Bridge Company purchased a $1.2 million, 40-door terminal building from a neighboring trucking company with the intent of leasing it to GSA for use by U.S. Customs for truck clearance. This offer was refused, and the Bridge Company then offered to sell the facility to GSA at cost.

The terminal building still sits vacant two years later, waiting for GSA, which prefers to purchase on its own terms. The Bridge Company offered in May 1979 to provide it without cost to the U.S. Government. GSA has also refused that offer. In contrast, truck examination on the Canadian side has run smoothly for many years, and was further improved in 1973 when its truck examination area was segregated from the rest of the terminal area.

CHANGES

Expressway Expansion Brings More Traffic

While the two decades of physical improvements on the Bridge were occurring, other developments near the Ambassador Bridge would bring dramatic increases in its traffic growth during the ’60s and ’70s. In 1970, Bridge car traffic started to drop because of the then two-year-old John Lodge Expressway, which carried car traffic directly downtown, and consequently, to the Tunnel. It was not until the mid-1960s that work began on construction of a leg of Interstate 75 that would run right by the Bridge.

The 1-75 stretch from Toledo to the Bridge opened in 1967. And by 1970, 1-75 had been completed north of the Bridge through midtown Detroit, providing the Bridge with a connection with the interstate highway system that was further extended with the construction of a stretch of 1-96 near the Bridge giving the Bridge direct links with I-75, I-96 and I-94.

On the Canadian side, the City of Windsor and the Province of Ontario rebuilt the four-lane highway leading into the Bridge late in the decade. New entrances and exits were built on the Bridge terminal to tie into the new highway in 1970. In 1965, two other developments further stimulated use of the Bridge: the U.S. – Canada auto trade pact, which caused a heavy increase in truck traffic of new cars and auto parts, and the opening of the new Windsor Raceway. Tolls have been increased just once since 1957 when car tolls were established at 60 cents and 10 cents a passenger.

In July 1971, those rates were dropped, and one all-inclusive toll of 75 cents per car, including all passengers, was established. At the same time, the former commuter rate of 45 cents and 10 cents per passenger was revised to the all-inclusive rate of 50 cents, with the purchase of a 40-ticket commuter book. These toll rates are still in effect today, as is the truck rate of 1 cent per hundred pounds, the rate filed with the first toll tariff in 1940.

Changes

In 1965, five years after stepping down as chairman, Joseph A. Bower retired as a director of the Detroit International Bridge Co. He was named honorary chairman. Ten years later, a second son, Joseph W. Bower, was elected to the Board, and succeeded his brother Robert as chairman in 1977. Both served as absentee officers of the Company. On August 15, 1977, Joseph A. Bower would die in his Florida home at the age of 96.

Gone was the man who had moved to Detroit at the age of two. He had left school after the fifth grade upon his father’s death, and went to work at the age of 10. He held three jobs simultaneously as a boy – office boy for ex-Circuit Court Judge William M. Lillibridge in the morning, porter and sales clerk in a sporting goods store in the afternoon and signal officer for the Detroit Police Department from 1 a.m. ’til dawn.

In the tradition of an earlier time, he “read law” under the judge, and passed the bar examination without a formal education. Determined to grasp the intricacies of finance as well, he entered the Detroit Business University.

At the age of 19, young Joseph was hired by the Detroit Trust Company. By 1924, the year Bower actually undertook the Ambassador Bridge project at John Austin’s urgings, he was a vice president of J. P. Morgan’s New York Trust Company.

His success was not that of a banker, but of a business man who understood finance. His was the proverbial knack for taking “lemons and making lemonade,” and his reputation for converting soured loans into solid accounts bordered on the legendary. Henry Ford turned to him during the Ford Motor Company’s fiscal crisis in 1921.

READY FOR THE FUTURE

The Bower family successfully maintained control of the Ambassador Bridge until 1979. When Joseph A. Bower stepped down as chairman of the Ambassador Bridge Company Board of Directors in 1939, he turned the reins over to his son Robert. Then, in 1979, following the death of Joseph Bower, the family decided to withdraw from the management of the bridge. On July 31, after two years of negotiations, the Central Cartage Company of Detroit purchased the Ambassador Bridge, which is owned and operated by the Detroit International Bridge Company.

Central Cartage was owned by a native Detroit family headed by Manuel J. “Matty” Moroun, a successful transportation businessman who recognized both the great heritage of the bridge and its great potential.

Many appropriate management changes occurred under the leadership of Moroun. Both he and Dan Stamper, current president of the Ambassador Bridge, set a vision for the future that involved immediate change and future growth. As much as the Bower family members were financiers and their expertise was needed during the building and early decades of operating the bridge, the 1980s were bringing new and different challenges.

It became apparent that new ideas and approaches were imperative to maintain the bridge’s position as one of the leading border crossings in North America. Moroun provided the imaginative leadership needed to accomplish this. He was an expert on international trade and transportation, and he demonstrated a keen ability to work with local neighborhoods as well as state, federal, and international governments. Furthermore, he understood the needs of the commercial truck companies, tourists, and travelers who used the bridge. And Stamper, also familiar with bridge operations and international trade, has provided the administrative leadership to make the needed changes to happen.

As in past decades, the bridge continues to be carefully inspected and excellently maintained. In order to alleviate the congestion caused by traffic tie-ups during certain weeks of the year, the company built a secondary truck inspection facility in Windsor, just three miles south of the bridge. Then, in 1993, a new truck exit ramp and an inspection facility on the U.S. side were added, followed by the construction of a new Canadian customs facility and new duty-free stores on both sides. In Windsor the duty-free store is operated in partnership with the University of Windsor.

Now in the advanced planning stages are a new bridge headquarters building, a major highway information center, and better access to the major interstate and provincial highway systems on both the Michigan and Canadian sides of the border. Bridge officials are working closely with neighborhood leaders to provide better housing and community facilities near the bridge. The Ambassador Bridge has also been selected under the North American Free Trade Agreement to install a model intelligent transportation system (ITS), using advanced technologies to automate customs, toll collecting, and other procedures that will facilitate international trade. Under the guidance of Moroun, the Ambassador Bridge Company is a private company that proudly serves the public.

The positive results of the current leadership of Moroun, Stamper, and the Ambassador Bridge’s board of directors are clear. Improved facilities and careful planning have made the Ambassador Bridge the number one international bridge crossing in North America. Nearly 10 million vehicles crossed the span in 1995.

The necklace of lights on the bridge’s cables, which is visible at night for miles in every direction, creates a dramatic presence for the Ambassador Bridge and shines as vivid testimony to its continued vitality as the world’s longest international suspension bridge.